The Microfiber Pollution Primer

You have heard about microfiber pollution, but what is it really? Where does it come from? Why is it happening? Where does it go, what are the dangers and who does it hurt? These are the fundamental questions of the microfiber pollution problem that will help you answer the last, most important quandary: What can I do to keep our ocean cleaner and prevent microfiber pollution? The scientific community has your back and is hard at work investigating the new problem. Read on to discover what is known and still unknown in the world of microfiber!

Updated 9/09/24. Click here to jump to the newest section on human health impacts from microfiber ingestion and inhalation.

What is microfiber? Give me a definition!

You’d think this would be an easy definition, but there are some subtleties. On one hand, you’ve likely heard of microfiber towels, cleaning tools or clothing. That is not necessarily, and certainly not exclusively, what we are talking about here. For the purposes of this primer and when thinking about microfiber pollution, we are talking about pieces of fiber, less than 5mm in length (5mm is approximately half the width of your pinky nail) that have detached from or broken off whatever they were part of (your shirt, a towel, a rug, a tarp, even from car tires) and are loose in the environment. Their diameter is less important, but they range from something you can see to so small they are only visible with magnification. The materials from which microfibers come are as diverse as the materials that exist on the planet from synthetics such as polyester, nylon, spandex, etc.; to naturally-derived materials such as cotton or wool. Another term to describe what we are talking about is “fiber fragmentation.”

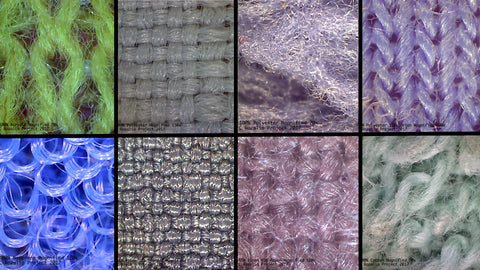

Image 1: Magnified images of various textiles with different weaves and materials. All are vulnerable to fiber fragmentation.

Image 1: Magnified images of various textiles with different weaves and materials. All are vulnerable to fiber fragmentation.

|

Note: this is not just about plastic! Why do we care about naturally-derived microfibers at-large in the environment? Unless something is certified organic down to the dyes, it is possible that it has associated chemicals that are harmful to our environment. The chemicals are added as dyes and to set the dyes, wrinkle releasers and optical brighteners. Have you ever heard of anyone drinking wrinkle releaser? Nope, we haven’t either and we don’t think anyone should. In fact over-the-counter wrinkle-releasers have warnings like “Do not spray on face” and “Do not take internally.” For those reasons and more you will read about below, we think it’s important to include ALL manmade fibers in this discussion and keep the ocean and our public waterways free of everything that is part of our clothing manufacturing process and laundry routines. |

How is microfiber created?

The creation of microfiber/fiber fragmentation occurs when we wear, wash and dry our clothes. Essentially, it is potentially happening all the time to all of the textiles we use and wear. That said, the washing machine is a significant creator of microfibers.

|

An average of 700,000 fibers per 6kg of clothing are escaping our homes and flowing out of our drains every load of laundry (Napper, 2016). |

Image 2: Washing machines do not have filters meant to stop microfibers and dryer lint traps are inadequate.

Rachael Miller and her colleague Professor Kirsten Kapp of Central Wyoming College investigated the expulsion of microfiber from dryer vents. They found an alarming amount of microfiber escapes the built-in filter to deposit on the ground - up to 30 feet from the exhaust and likely much farther if carried in the wind (Kapp and Miller, 2021).

Our first-hand experience has taught us that there is a significant amount of microfibers coming off clothing as they are being worn and used. Microfiber research is one of the more difficult types of research to carry out. It’s not because there are harsh chemicals or fragile equipment involved. The reason is because of microfiber contamination shedding off researcher’s clothing. In our efforts to identify the existing environmental presence of microfiber pollution, there must be painstaking measures taken to protect samples throughout collection and processing.

Where are microfibers found?

The short answer is everywhere. Microfibers have been found in samples in every body of water, from lakes, rivers and ocean to the most remote areas of the arctic and deep sea. Here are some papers that look at microplastics in a wide variety of ecosystems and geographies: Dong et al., 2020, Alfaro-Núñez et al., 2021, Ross et al., 2021, Barrett et al., 2020.

Our own team has been investigating microfiber and microplastic pollution in rivers. On our expedition on the Hudson River, led by Cora Ball founder and co-inventor Rachael Miller, we found microfibers high up in the Adirondacks all the way to where the Hudson reaches the Atlantic Ocean - even where no one lives (Miller et. al., 2017). The length of the Snake and Lower Columbia rivers were sampled for microplastic and microfiber by Rozalia Project guest scientist and partner, Professor Kirsten Kapp with similar results, finding microfiber pollution in rural and urban areas of the rivers. (Kapp and Yeatmen, 2018).

Image 4: Heat map of microplastic concentrations measured on our Mountains to the Sea expedition on the Hudson River. (Miller et al., 2017)

Scientists are also looking at microfibers in oceanic surface waters. A global characterization (Suaria et.al., 2020) sampled in 6 major ocean basins and found that the majority of fibers found in the ocean are cellulosic (most often cotton). This demonstrates a surprising persistence of natural microfibers - and another reason we keep naturally-derived fibers on our keep-out-of-the-ocean list.

|

Synthetic microfibers in the marine environment: A review on their occurrence in seawater and sediments summarized the situation by saying “microfibers are present worldwide in marine sediments and seawater” and “[microfibers] represent the most important percentage of microplastics, up to 100% [of a sample]” (Gago et.al., 2018) |

Microfibers are being eaten by sea creatures

It appears that, in most cases, when scientists have looked for microfiber in sea creatures, they have been found. Studies include mussels in coastal and freshwater environments (Christoforou et.al., 2020 and Doucet et.al., 2021), crabs (Watts et.al., 2015), plankton (Cole et.al., 2013) and fin fish (Rochman, 2016).

The studies above established the presence of microplastic, mostly microfiber in a variety of species. In order to observe potential impacts of ingestion, scientists are studying creatures in labs.* The result of consuming the microplastic is varied:

- Plasticizers within plastics and adhered (stuck to the surface from the environment) persistent organic pollutants can transfer into the creature and act as endocrine disruptors

- Microplastics, especially microfibers can become tangled and remain within stomachs, taking up space instead of food and reducing the amount of food intake

- Even when the plastic passes through the digestive system, there is no nutritional value derived from the time spent feeding on the fibers.

|

A combination of these factors has resulted in a measured reduction of reproductive viability (fewer offspring). |

*Important to note: in lab studies, microfiber/microplastic concentrations are often greater than in typical environmental conditions.

Image 5: Fluorescent microplastics photographed within plankton. (Cole et al, 2013)

Microfibers are in our food - that means your food, too!

Not only are microfibers being found in the environment and sea creatures, they are being found in the foods we eat at home. Microplastics are in honey, salt, seafood, beer, tap water (Orb Media) and bottled water (Mason et.al., 2018). Seafood tested in a California fish market found microplastics in 25% of finfish and 33.7% of shellfish. (Rochman et. al., 2015)

A 2019 report estimated that the average person consumes the microplastic equivalent of a credit card every week, the majority coming from drinking water (World Wildlife Fund, 2019).

Image 6: Microplastics have been found in tap and bottled water, honey, salt, beer and in many seafoods.

Microfibers are in us.

Scientists are finding microfiber in human feces, blood, and deep in our lungs. The presence of microfiber and microplastic in our bodies has not been conclusively linked to any disease or illness, but we know based the lab studies on microplastic and aquatic animals, that there is a potential for harm

In 2018 the first group of scientists examined human excrement and found microplastic in the samples provided by eight volunteers for the pilot study (Parker, 2018).

Another pilot study in 2022 revealed that microplastic is being transported throughout or bodies in our blood (Carrington, 2022). This has prompted many more questions by the public and the medical field to investigate how the microplastic may impact our organs and cell functions.

Microplastics found in 11 of 13 lung tissue samples raise similar questions about what long-term microplastic exposure and accumulation in our lungs could mean for chronic disease development (Uildriks, 2022).

2024 UPDATE - New data shows health concerns correlated with the presence of microplastic in humans:

- Correlation between presence of microplastics in the human body and a disrupted gut microbiome/digestive issues ( Pinto-Rodrigues, Science News March 23, 2023 )

- Reduced fertility ( Hu et al. 2024 )

- Presence of microplastics in arterial plaque was associated with increased chance of experiencing stroke or heart attack ( R. Marfella et al. 2024 )

OK, I understand that my laundry causes microfiber pollution. What can I do about it?

Take action against microfiber pollution by taking control of your own laundry. Use a Cora Ball to make a difference in your home or at a laundromat. Cora Ball addresses all clothes in the load while your clothes get cleaned just like normal.

|

While reducing microfiber pollution by 31%, Cora Ball is also preventing microfibers from breaking off clothes in the first place (Napper et. al., 2020). |

After-market washing machine filters can be installed as part of your washing machine plumbing. These kinds of filters address all of the water, and must be emptied often. Use it in combination with Cora Ball to protect your clothes and stop the highest percentage of microfiber at the same time.

Update your washing habits to lower microfiber pollution

- Wash less: unless you are truly getting dirty, wear clothes multiple times before tossing them in the laundry hamper and spot clean when you can. This will have the added bonus of saving on your water and electric bill!

- Use cold water: warm and hot water cause more microfiber shedding than cold water, so use cold water washed unless absolutely necessary. TIP: If you are switching to cold water washing, consider a new cold-water wash-dedicated laundry detergent - your clothes will get just as clean as before and you’ll save money on your gas/electric bills!

- Fill your washing machine ¾ full to full. Full or almost full loads of laundry produce less microfiber pollution.

- Lower rpm in the spin cycle: not every washing machine has the option to change spin speed, but lower speed is better.

Your voice has power!

Work with brands. Communicate with your favorite clothing brands that you’d like to see more resilient clothing. This can influence brands’ manufacturing and purchasing decisions and challenge their suppliers to do better too.

There are no built-in filters for washing machines available on the market and we have seen that dryer lint traps are also not adequate for preventing microfiber pollution. Speak up and ask the big companies to change the status quo. There’s an opportunity for a small shift at a high level to make a huge change to the problem of microfiber pollution.

And don't forget to spread the word! Tell your friends, family and community what is happening and how they, too, can be part of the solution.